A Ride of a Lifetime

On a gurney, being hoisted into an ambulance, hearing only Russian voices.

Welcome to a newsletter themed at the intersection of longevity and wine history. 🍷

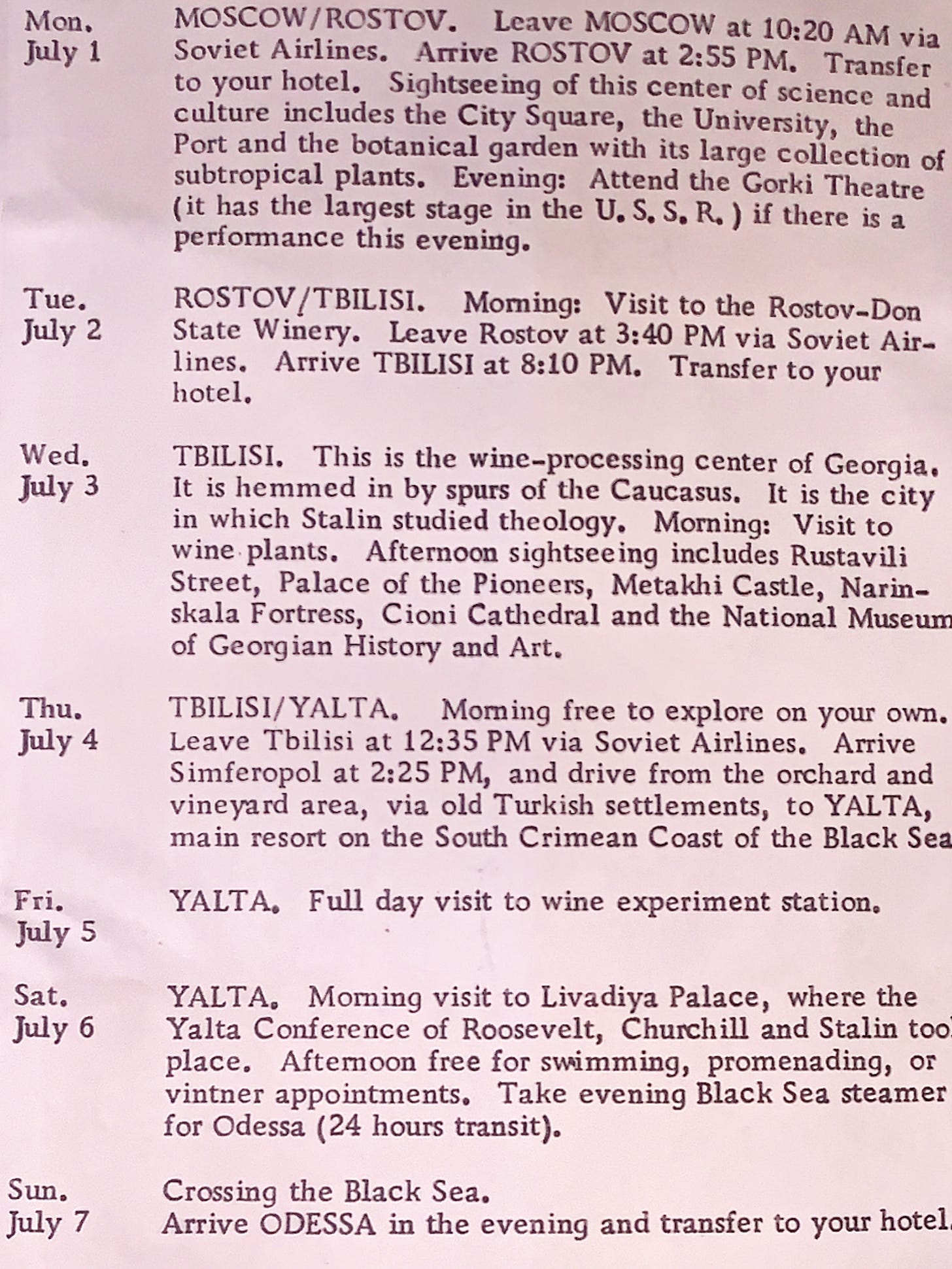

1963: Mario Gemello heading off to tour Soviet Union wineries.

This was no ordinary Fourth of July for my grandfather, Mario Gemello.

He spent the afternoon throwing up in the hotel bathroom of a foreign country. After a while his traveling companions, eight winemakers from California, decided they better get him to a hospital. Next thing he knew, he was on a gurney, being hoisted into an ambulance, hearing mostly Russian voices.

It was 1963. Three months before his 47th birthday.

Earlier in the day, he had sent a postcard to my grandmother about the great time he was having, touring wineries and vineyards behind the Iron Curtain. This was Day 14 of a month-and-a-half long trip of mostly Soviet Union and Eastern Bloc countries.

“Hello from Yalta in the Black Sea,” he had written in the postcard that morning, referring to the resort town on the south Crimea coast, part of the Soviet Ukraine, during that era. “Still holding out real well. Tomorrow we take the boat ride on the Black Sea.”

Mario and his companions had just flown in that morning from touring the wine-processing center of Tbilisi, Georgia, where Joseph Stalin studied theology, however briefly, before giving up priesthood ambitions and quitting school altogether.

On the Crimea Peninsula, Mario and his crew toured the orchard and vineyard of Simferopol in the morning, then visited the Livadiya Palace, where Franklin D. Roosevelt, Winston Churchill and Stalin held the Yalta Conference at the tail end of World War II, negotiating the split of Germany and Eastern Europe.1

Either during or sometime after the tour, my grandfather’s stomach started to turn.

“It finally caught up with me at both ends. I got real sick to my stomach and was given a quick ride to the hospital for treatment,” Mario wrote in his travelogue. “Now this is the topic of conversation, because I am different from the rest.”

The summer trip was sponsored by the Wine Institute, a California advocacy group, and started with a pitstop in Washington D.C. to get briefed on foreign policy at the State Department. The United States was less than a year removed from the Cuban Missile Crisis, when the Soviet’s threatened to put nuclear missiles ninety miles off the coast of Florida, until President Kennedy ordered a naval blockade around the Caribbean Island-nation.

A page from Mario's USSR trip scrapbookLuckily, the Russian doctors tending to my grandfather held no grudges and had him ready to return to his hotel within two hours.

This was after 10 days of living it up in Russia. The nine California winemakers kicked it into another gear following a “disappointment” in their first Russian hotel in Leningrad.

“It was real old and dirty,” Mario journaled about the The Europa Hotel, “but the rooms were big enough to be a dance hall.”

That inspired Mario’s comrade Jeff Physer to complain to his Berkeley travel agent via wire. A few days later, all accommodations got upgraded to “Deluxe Class,” with comped champagne, beer and sometimes cognac included with dinner.

With any airline delays, the group found ways to maximize their enjoyment. The morning they were flying from Rostov to Tbilisi, they were told their flight was delayed four hours. They found a piano bar with morning hours or at least a manager willing to open for them.

“So we are playing piano, singing, playing cards and trying to start a cocktail party,” Mario journaled. “We ended up not leaving for Tbilisi until 3 pm.”

Part of the travel agendaWhatever hit my grandfather’s stomach four days later in Crimea must have been something far more wicked than one too many champagne flutes, because impromptu cocktail parties were not unusual with this traveling crew. But they sure had fun teasing him.

“Our guide Nina was a doll throughout the [post-hospital visit] experience. I’m now known as the problem child of hers,” Mario journaled. “With no supper, no drinks and no good time, I went to bed early to recover for the boat ride tomorrow on the Black Sea.”

In his travelogue the next morning, he assured his future self or any other eyes peeking in his journal that he rebounded.

“We were up early this morning, and I’m in good shape again. Departed at 9 am. Had breakfast on the ship, walked all over the four decks. At 6 pm, we had dinner, dancing. At 7 pm, we ate again,” he journaled, signing off that they “arrived at Hotel Odessa at about 9 pm.”

The next morning, he gave high praise to the Ukrainian city of Odessa, the Soviet Union’s second most important seaport, only to St. Petersburg.

His crew toured a local winery, then set off on a two-hour city tour, which inspired my grandfather to write home in a postcard, “Very beautiful here in Odessa. Getting a real education.”

Mario’s far from alone in admiring the beauty of Odessa, which is located on a hill slope that descends via the “Potemkin Stairs” into terraces to the Black Sea. The steps were immortalized in the 1925 silent film “Battleship Potemkin.” Also, Mark Twain admired a statue, at the top of the steps, of Duke of Richelieu, the city’s first governor. In his 1869 travel book, The Innocents Abroad, Twain wrote:

It stood in a spacious, handsome promenade, overlooking the sea, and from its base a vast flight of stone steps led down to the harbor—two hundred of them, fifty feet long, and a wide landing at the bottom of every twenty. It is a noble staircase, and from a distance the people toiling up it looked like insects.2

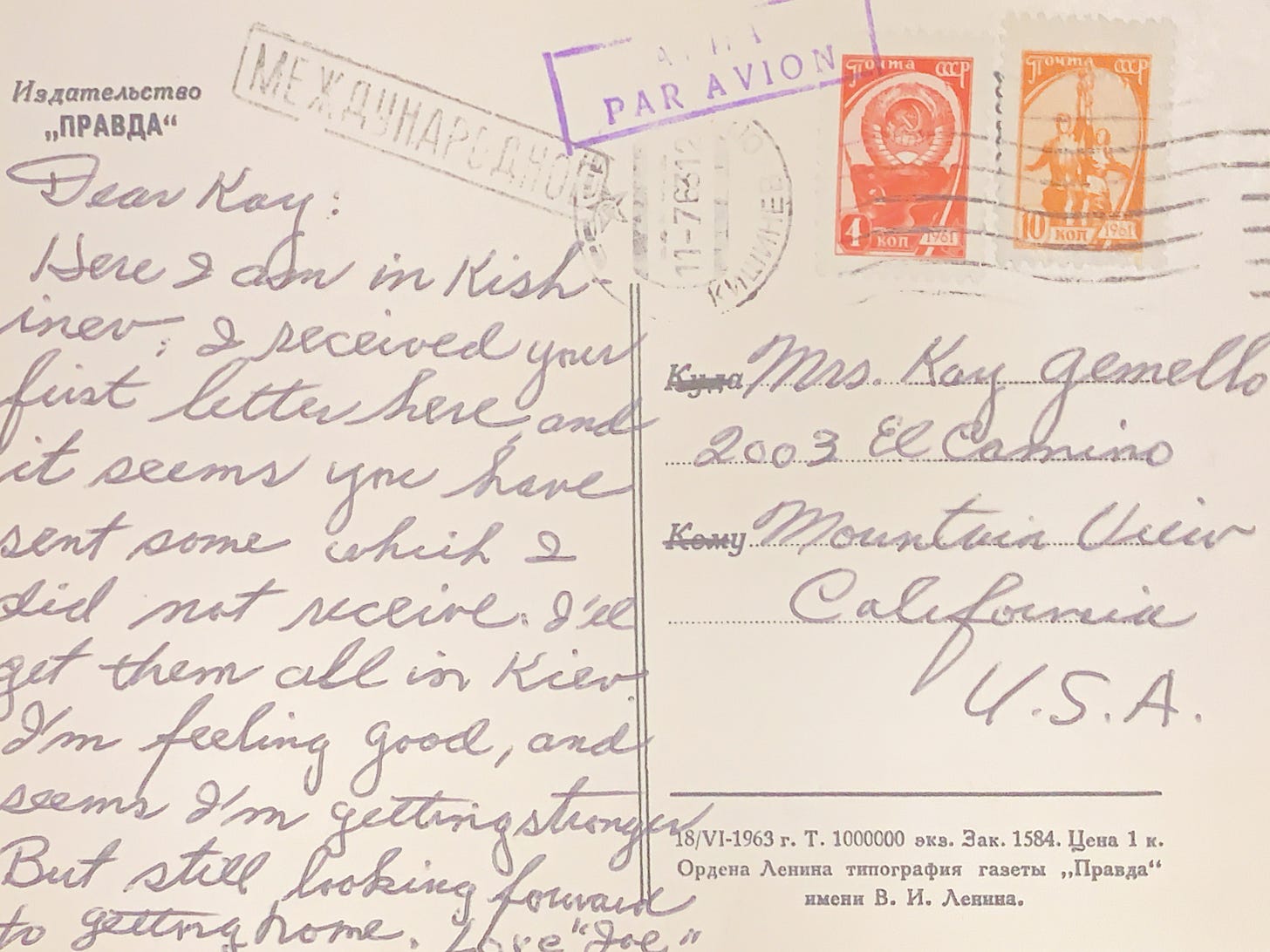

After Odessa, Grandpa Gemello and his crew took a three hour bus ride east for a winery tour in Kishnev, the capital of Moldova. He sent postcards home everyday of the trip. But it wasn’t until he arrived in Moldova, one of the letters from home caught up to his traveling schedule.

“Here I am in Kishnev. I received your first letter here and it seems you have sent some which I did not receive. I’ll get them all in Kiev,” he wrote, referring to Ukraine’s capital, the last leg of the Soviet portion of the trip. “I’m feeling good and it seems I’m getting stronger. But still looking forward to getting home.”

He alternated sending postcards to Grandma Kay and his three children.

“I hope you are keeping the winery going,” he wrote to his 10-year-old son, Mark, in a postcard, picturing his hotel from Bucharest, Romania. “If you need me, I’m two doors down from the corner on the right side.”

He addressed it to his fourth grader: Master Mark, Managing Director of Gemello Winery.

If you’re new here—hi, I’m Kevin!

I’m the author of 🍷 Rain on the Monte Bello Ridge,🍷 my forthcoming memoir about health, aging and winemaking. (Read the origin story of the book.) 🍇

The Centenarian Playbook is my newsletter, which features:

Healthy aging/longevity tips and stories from Grandma Kay’s long life.

Wine history & stories of the Gemello Winery

Ancestry & family research tips

The Yalta Conference, Office of the Historian, U.S, State Department

Twain, Mark, The Innocents Abroad, New York and London, Harper & brothers, Chapter XXXVI