Two Guys from Italy

A re-acquaintance of two Northern Italian immigrants in a San Jose saloon one night in 1912 would be a pivotal point in John Gemello’s life.

👋 Hello, I’m Kevin Ferguson, author of 🍷 Rain on the Monte Bello Ridge,🍷 a memoir about health, aging and winemaking. (Book summary) 🍇 This is my newsletter. It includes book research and early release chapters about winemaker Mario Gemello and his centenarian widow, Kay Gemello. 📖 They are my lovable maternal grandparents. You can subscribe by clicking on this handy little button.

Below is a middle chapter, which immediately follows April 3rd’s post, The Luck of the Italian, about the circumstances in Italy that would nudge my great grandfather, John Gemello, towards emigrating to America in the early 1900s.

Two Guys From Italy

In 1905, my great grandfather John Gemello was rejoined by his wife, Teresa, while he was working in the German mines, but it was a short-lived reunion. Teresa moved back to Piedmont the following year when two life-altering experiences occurred. Her mother passed away in December. Around the same time, she learned of her second pregnancy, Marguerite.

By 1907, John returned to the Piedmont region of Italy as well and bought two acres for planting his own grapes. He tended to his own vineyard in the evening, after returning from his day job, working at the Martini and Rossi Asti vineyard, which produced sparkling wine. This was a place, he never fully left.

In 1911, his own vineyard started to produce grapes. A hail storm came that year and was so powerful, it wiped out the crops. It frustrated John, in fact, so much, that he contemplated leaving the region again, perhaps for good.

He told his wife he wanted to go back to Germany in the mines, but Teresa vetoed the idea.

“It’s too dangerous,” she said. “Why don’t you go to America?”

John said he liked that idea, but if he was in France or Germany, he could come home in ten hours to visit, but in America it would take three weeks.

“Go to America and I’ll stay here with my father. If you like it there, I’ll come out later,” she told him.

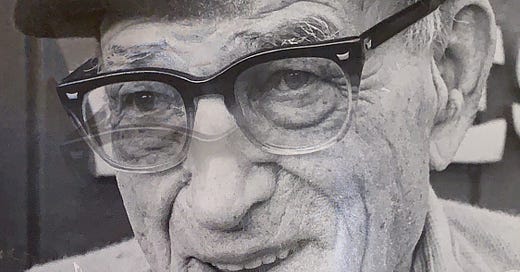

John Gemello, 98, in 1980In December of 1912, John left Italy, and arrived in San Jose, California, two or three days before Christmas.

Within a few months, John would land a job at the Almaden Vineyard, which was located in San Jose at the time. Jobs included pruning the vineyard and sometimes hauling wine up to San Francisco in a horse-drawn wagon, a transportation method that would get replaced by trucks in 1918.

One day, the foreman asked him if he could plough a field.

“Of course,” he said. “I used to do that all the time.”

“Great, but I need you to plough as close to the vines as possible, so there would be nothing to hoe by hand.” That he did, and the foreman was so pleased, he told him to do the whole vineyard, a process that took two weeks.

After completing the project, John and his team went to celebrate at the Costa Hotel,1 a popular San Jose watering hole for Italian immigrants.

That night, John bumped into an old friend, whose family he knew from Piedmont, Italy. His name was Giovanni Beltramo.

“What are you doing here?” Beltramo asked. “I didn’t know you were in America.”

That re-acquaintance of two Northern Italian immigrants would be a pivotal point in John’s life.

Giovanni Beltramo in his Atherton vineyardThe Loan

Like John Gemello, Giovanni Beltramo came to America because a friend and Piedmont-native wrote him about opportunities in the Santa Clara valley.

Beltramo’s voyage took place 32 years earlier than Gemello’s. Armed with Italian vine clippings, Beltramo left Piedmont for California in 1880 and settled in the little dusty village of Menlo Park, which had been growing with railroad workers and summer homes for San Francisco’s wealthy ever since its new train depot opened in 1863.

That’s perhaps where Beltramo met John T. Doyle, a San Francisco lawyer, who had built a summer mansion in Menlo Park. Doyle hired Beltramo to supervise his Cupertino Vineyard on his country estate in the Santa Clara valley.

Doyle made a fortune2 as chief counsel to the Archdiocese of San Francisco. His country estate had two wineries. When he decided to put a post office on the western winery, he named it “Cupertino” to distinguish it from other post offices on the peninsula.

Doyle’s winery was advanced for the time. To process his grapes into wine, he used water from damming up sections of the Stevens Creek, a 20-mile long channel, originating in the foothills of the Santa Cruz Mountains in what is now the Montebello Open Space Reserve. It flows southeasterly through Cupertino, Los Altos, Sunnyvale and Mountain View before emptying into the San Francisco Bay. Doyle created pumping stations all along the creek. His water system would become the basis for the city of Cupertino’s municipal water system.3

Cupertino map - provided by the Cupertino Historical SocietyVineyards were the lifeblood of this region’s early economy.

After a couple of years working for Doyle, Beltramo pursued his own vineyard, purchasing 3.5 acres in Atherton for such an endeavor. It would include a small wine store.4

Eventually, Beltramo and his wife would expand the Atherton property for a side hustle, converting the home into a boarding house for Italian immigrants. He’d ride the train to San Francisco and recruit Italian immigrants seeking work and mingling at the Garibaldi Hotel. He’d tip them off to the opportunities down on the peninsula and offer them a room to rent closer to the jobs.

When he wasn’t tending to his vineyard or trying to fill his boarding rooms, Beltramo would occasionally hang out and play cards at the Costa Hotel in San Jose.

One of these nights in 1912, Beltramo ran into John Gemello.

“What are you doing here?” Beltramo asked.

Gemello told him he’d been in California for less than a year, but didn’t have the money yet to send for his wife, Teresa, and Margurite, his five-year-old daughter.

Beltramo, who was 53 at the time, asked the 30-year-old Gemello if he had hoped to bring them, later. Gemello said yes.

Beltramo knew all too well the challenges of trying to make it alone in a new world. He offered to loan Gemello the money, $190,5 for first class tickets from Italy to San Jose.

Gemello graciously accepted the loan and sent Teresa a telegram informing her he had arranged for her and Margurite to come to America. In the next three years, she would have sold her Piedmont property and most of her possessions. She would also put her father in a home, before arriving in San Jose by 1915.

The reunited Gemello family moved into a house on Montebello Road, renting from the brothers of the Picchetti Winery, Antone and John. Their father, Vincenzo, and uncle Secondo were among the earliest settlers on the ridge, and are credited with naming it Montebello, Italian for beautiful mountain.

John Gemello spent that winter planting a vineyard for the Picchetti brothers. Meanwhile, Margurite attended class just up the long and winding hill with the kids of the other ranch families at Montebello School.6 At nine-years-old, she likely sat in the small three-room schoolhouse surrounded by classmates and a few of their siblings, wondering if she would be a big sister some day. Little did she know, little Mario, my grandfather, was on his way that year.

Around 1917, Gemello partnered with two others running a small orchard and vineyard on the Montebello ridge. Within one or two years, they earned $9,0007 each, largely due to the high prices for fruit following World War I.

Life was good.

Then, in 1920, things took a turn as Prohibition hit, banning the sale of alcohol.

Do you like this newsletter?

Then you should subscribe here:

Costa Hotel no longer exists, but it was located near Henry’s World Famous Hi-Life on West St. John Street.

John Doyle had several big court cases. In one case for the archdiocese, he settled a century long fight with multiple kings of Spain, who ordered the Jesuits to possess California in the name of the crown. Doyle was fluent in Spanish and spent years studying treaties, Spanish and California history, and documents that were in Mexico City. In 1870, he presented his case before an American-Mexican Claims Commission and won a judgment of $904,700. Source: Almanac News, The Pious Fund article

Doyle dammed up parts of Stevens Creek. Source: City of Cupertino

Beltramo’s original Atherton wine store would later get expanded, moved to Menlo Park and renamed Beltramo’s Wines and Spirits, run by multiple generations of Beltramo family members for 134 years. It eventually closed in 2016. Giovani’s great granddaughter and store GM, Diana Hewitt, noted about the closure to the press that year that her uncle was 82 and her dad was 79. “They deserve to go fishing.”

A first class ticket costing $190 in 1912, would be equivalent to about $5,600 in 2022. Source: CPI calculator

Montebello School was built and supported by the Picchetti family in 1892. It later became part of the Cupertino school district. The district, unfortunately, closed the school in 2009, due to declining enrollment, after 117 years. Source: SJ Mercury News

The value of $9,000 in 1919 would be the equivalent of about $146,000 in 2022. Source: CPI Calculator

Kevin, This was such a fun read for me, because I know and live in the area. I worked in Menlo Park and went by Beltramo's all the time.