The Great Prohibition Caper

The Bargetto brothers had a secret. A meddling neighbor tried to expose it.

👋 Hello, I’m Kevin Ferguson, author of 🍷 Rain on the Monte Bello Ridge,🍷 my forthcoming memoir about health, aging and winemaking. (Read the origin story of the book.) 🍇 The Centenarian Playbook is my newsletter, which features longevity tips and stories from Grandma Kay’s long life. It also includes stories of the Gemello Winery, which her late husband, Mario, ran for nearly half a century. 📖 I’m sure you’ll find my maternal grandparents are quite lovable characters.

How the Bargetto Brothers Duped the Feds

When Prohibition swept the country in 1920, Great Grandpa John Gemello resorted to what many Italian immigrants did: pivoted to harvesting vegetables instead of grapes.

Luckily, the First World War had driven up the price for vegetables. Therefore, he was able to get a good deal in 1919 for his vineyard on Montebello Road in Cupertino. Gemello used part of that money to buy a 30-acre vegetable ranch in Mountain View. He then partnered with a few others in purchasing a number of trucks for delivering produce house-to-house throughout the south Bay Area.

Around 1925, Gemello took advantage of an obscure loophole in Prohibition law that allowed him to produce up to 200 gallons of wine (four barrels) a year for “home use.” In other words, for the family to drink, and not sell.

About 40 miles southwest in the Pacific coastal town of Soquel, Giovanni and Filippo Bargetto, Italian immigrant brothers also from Gemello’s native Piedmont, were doing something similar: transitioning from winemaking to peddling fruits and vegetables to homes in the Santa Cruz mountains.

This photo of me was taken in June at the Bargetto Winery tasting room in Soquel. They also have one in Monterey. The winery officially opened for business in December, 1933, the same month Prohibition ended. It’s one of the longest continuously running wineries in California.

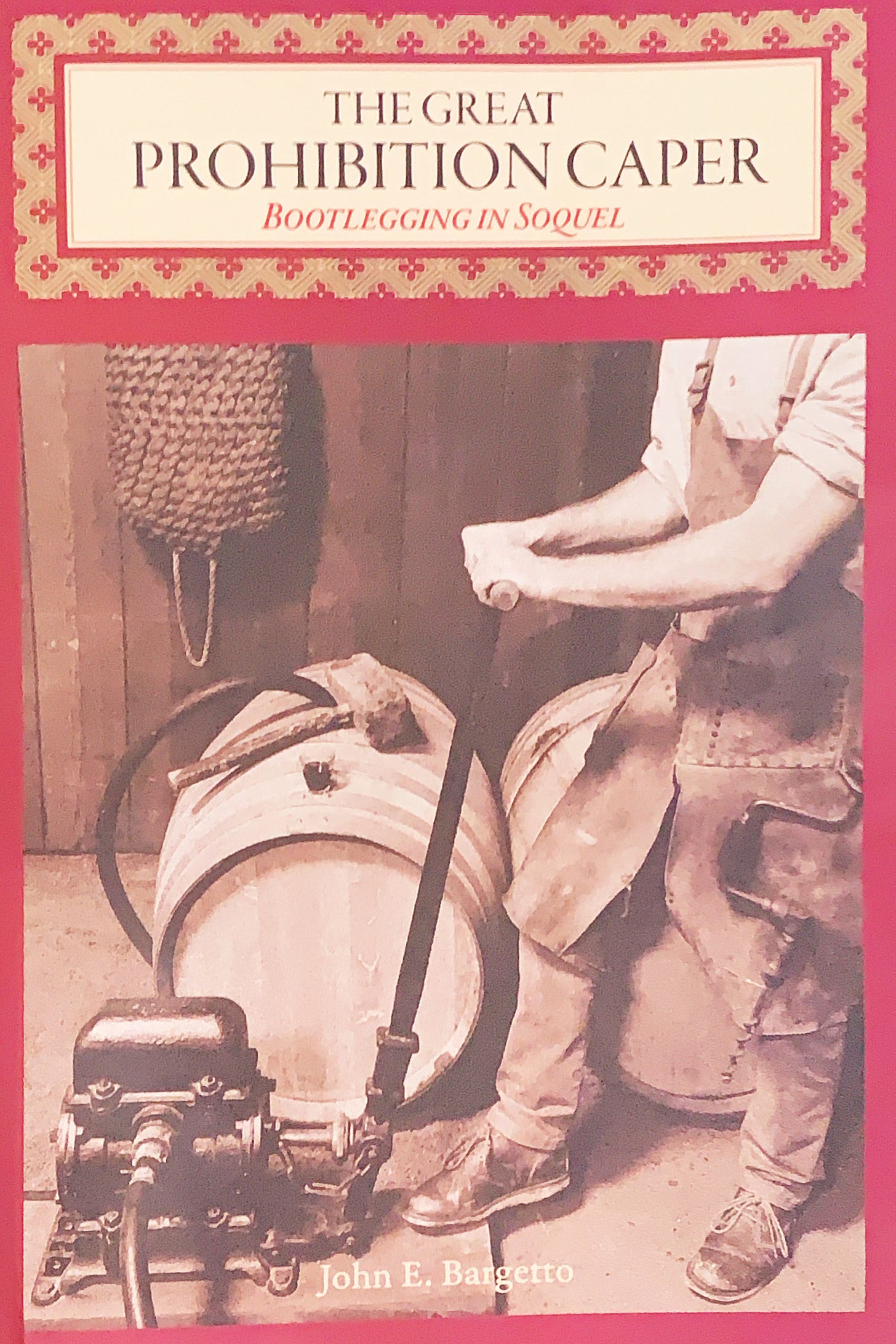

John E. Bargetto, Giovanni’s grandson and family historian, calls the operation a “sort of a traveling farmer’s market,” in his book, The Great Prohibition Caper: Bootlegging in Soquel.

Spoiler alert: as the title suggests, Giovanni and Filippo1 eventually take a chance on ramping up wine production beyond the approved four barrels for family consumption, gambling on the poorly funded and understaffed federal Treasury Department in charge of enforcing Prohibition law.

It’s quite a fascinating tale that John Bargetto, third generation owner of Bargetto Winery, tells of his grandfather and great uncle. He weaves documented historical research with what he describes as “occasional family lore.”

For six years, Giovanni and Filippo had abided by Prohibition law. But in 1926, they rolled the dice, producing six extra barrels and selling out in one month.

In the fall of 1927, they got even bolder, producing 22 barrels of wine. That accounted for 1,000 gallons, bottling the wine in gallon size jugs. The price: $1 per jug, generating $1,000 in revenue.

As all good stories need a villain, The Great Prohibition Caper found one in the “nosey Mrs. Pringle,” a neighbor up the road, who the brothers suspect tipped off the feds.

She was “an active member of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, one of two leading national organizations that pushed Congress to pass the 18th Amendment. The other was the Anti-Saloon League,” writes John Bargetto.

“[WCTU] wrote letters to the editor of the local paper and held meetings in the Soquel Grange Hall,” John Bargetto adds.

The Great Prohibition Caper is available online or by visiting one of the two Bargetto Winery tasting rooms.

One day, an old Studebaker rolled up to the Bargetto property. “Two serious-looking men in suits” popped out, and approached Giovanni and Filippo, who were hanging out in the yard. The men flashed their Treasury Department badges and introduced themselves. A heavy-set federal inspector said his name was Jackson. His partner was McKerney. They said they were there to inspect the property.

“Inspection? What the hell for?” Filippo asked.

“We have received reports of intoxicated beverages on this property,” McKerney said.

McKerney picked up a wooden mallet and knocked off the wooden bung of the nearest barrel. Jabbing his finger into the cool red liquid, he tasted it. “Yep! It’s wine,” he told his partner.

What he said next sounds like a Barney Fife line from the 1960s “Andy Griffith Show.”

“You Bargetto boys are lucky,” McKerney stated, as if he were doing them a favor. “It’s getting late and we don’t have time to deal with all of this right now. But we will seal these barrels and come back for them later.”

They stamped each one with a “United States Treasury Seal.”

“Now, don’t touch these. We will be back to deal with them soon enough,” McKerney added.

“Now, don’t touch these. We will be back to deal with them soon enough,” McKerney said.

The next morning, the brothers rose early, hurried through breakfast and immediately went to work. They gathered all the garden hoses they could find from all the “right” neighbors. In all, they needed more than 600 feet.

Justin Brown, a friendly neighbor, agreed to store the wine in the barn behind his house. The Bargetto brothers lined up 22 empty barrels in the barn, linking garden hoses together using old pliers to ensure that the connections were secure.

While Giovanni connected all the hoses across the yard, Filippo removed the steel bands from each barrel. After flipping each barrel upside down with a hand-cranked wood drill, he slowly punctured a clean hole through the barrel for connecting the hoses.

“The wine was moved manually by pumping back and forth on a long vertical bar attached to an oak handle. Pulling back on the pump handle allowed the cavity to fill with wine,” John Bargetto writes.

The men then refilled each drained barrel with water. This process took all night, the men working under oil-burning lamps for light, because the barn had no electricity. By 4:30 am, they had pumped the last barrel. The containers filled with wine-tainted water were rolled back into place with the oily tarp pulled over.

Ten days later, Jackson, the heavy-set federal inspector, returned by himself unannounced.

“I have a signed order from headquarters to destroy the 22 illegal barrels of wine. But before I do, I have some documents for you to sign.”

Pretending to be mildly annoyed, Giovanni read the documents then signed them.

As Jackson watched contents from the barrels drain out and flow into the nearby creek, he became suspicious.

“This wine’s color is awfully [clear],” he observed.

“Well, that’s right, it was a bad vintage!” Giovanni claimed.

Jackson frowned thoughtfully, but he had more inspections to perform. There was no time to push the issue. Returning to his car, he drove off, never to be seen again.”

There are three buttons at the bottom of every post: “like,” “comment,” and “restack.” Restacking is sharing in digital form. It goes out to the Substack community. If you enjoy the content and click “Restack,” it helps a lot.

At one point in the 45-page short story book, author John E. Bargetto described the brothers adopting American customs, including Americanizing their names to Johnny and Philip. To minimize confusion in this blog post, I continue to refer to the brothers using their Italian names, since both the author’s and his grandfather’s American names are John.

Ha - great story! Thanks, Kevin!

This is a terrific, entertaining story! Thanks Kevin!